The shaper - A golf course designer’s most important tool

In order to create great golf an architect needs a number of things. He needs a great site and a great plan as well as a generous and understanding client, a clear vision for the finished product, some daring and a strong dose of artistic flair. Most of all, though, he needs a talented shaper.

With the odd exception, course designers rarely give credit to the people behind the scenes who physically get their golf holes built. The construction team is an essential part of golf course architecture, not only ensuring the design vision comes to life but also that future owners and superintendents are able to operate the golf course in a practical and efficient manner. Holes and features must look good, but also drain well and be easy to maintain.

While there can be as many as a dozen or more people on a construction crew at various stages of development, generally there is one lead shaper in charge of any particular project. This is the guy given the not insignificant task of building tees, greens, bunkers and fairways according to a set design vision. A poor or lazy shaper can break a project, but a good one can make the difference between solid golf and special golf, and elevate holes to a level they may not have reached.

Such is the case with the exciting new coastal course being built at Cape Wickham, on King Island in Tasmania. There, an unassuming industry veteran named Lindsay Richter (right) has been working away for more than a year; in charge of what his design and construction colleagues hope will become one of the world’s most memorable golf courses. It’s too early to tell whether the Cape Wickham project will be a financial success, but not too big a stretch to suggest that without Richter it would have almost certainly been a failure.

Richter works for the Programmed Turnpoint Group, a golf course building company founded in 2002 by Andrew Purchase. He was the first full-time shaper employed by Purchase and has remained with the company for over 12 years. Says Purchase of his number one man, ‘Lindsay is the complete all-rounder. He can drive any machine - bulldozer, bobcat, excavator etc – he reads plans well, is brilliant at moving water away from problem spots and identifying design issues on paper that might not work so well on the ground. His greatest strength, however, is his temperament. Lindsay doesn’t get flustered. He’s very patient and communicates well, which is often half the battle.’

Richter got his start in golf by accident back in the early 1980s, while working as a bobcat operator in the landscape department at Queensland’s Kooralbyn Resort. Course designer Ross Watson was engaged to renovate the Kooralbyn greens, using Richter and the resorts own bobcat for the project. After one green Watson was impressed enough to invite him to go to Perth to work on The Vines, but his newfound shaper refused. ‘To be honest, I hated that first green’ says Richter. ‘The designers were so finicky, half an inch off here, half an inch on over there…and I just wasn’t very good at it.’

Things changed for Richter as more greens were completed. ‘Greens were all we did during that project’ he says, ‘and after a couple more I found my feet. I’ve loved it (golf course shaping) ever since.’ Working mostly with Watson and Graham Marsh during the early years, Richter’s resume includes more than 30 projects in Australia as well as courses in Malaysia, Indonesia, China and the Philippines.

A good shaper is part-artist, part-problem solver. He needs to be able to predict problems before they arise, whilst remaining nimble enough to solve those that arrive without warning. He must be capable of both managing and motivating his men, while also dealing with the ego of the designers, the owners, the consultants and others. It can be a thankless task, and some of the shaper’s most important work goes completely unnoticed, even by those intimately involved in the project.

The challenges thrown at the Programmed Turnpoint crew down on King Island have been considerable, and extend well beyond the usual issues with weather, budgets, drainage, design and the isolation of island life. There were times when the project seemed damned, and others where incredible holes risked failure because of design error or inexperience. Richter’s calm and easygoing nature have helped diffuse many a tense situation and allowed him to think his way clearly out of a design or construction pickle.

The construction process itself has been most unusual, in that concepts exist for holes but details are finalised on the ground. Richter plays a major role in the finished product, therefore, and has enjoyed the freedom of not having to stick to set plans or construction corridors. ‘A lot of the time you just get told by the architect what they want,’ he says, ‘but here at Cape Wickham its been great because we’ve been able to have a bit of say’.

That say includes advice on crucial areas like drainage, irrigation, bunker design, green contours and vegetation management. Often his own suggestions create additional work for himself, but Richter wouldn’t have it any other way. ‘You get a much better product when you take the time to get things right in the field,’ he says, ‘and not just build off a plan. Most developers don’t care about those little finishing touches, but they are what really improves a course and makes it great.’

At Cape Wickham the design changes and important finishing touches have come thick and fast for Richter, as each hole has been uncovered, debated and slowly caressed to life. Whether he’s starting from scratch or rebuilding something for the third or fourth time, his standard response to any design alteration is, ‘no worries, its only dirt’. For Richter, frustration and aggravation are apparently foreign concepts. Says Purchase of this easygoing nature, ‘where some shapers are dogmatic and stuck in their ways, Lindsay’s flexibility and personality make him very easy to work with and for. On top of everything else, he’s just a lovely person.’

Richter’s on site work mates are similarly fond of the man they affectionately call the ‘Big Dog’. A close knit crew they admire not only his skill on a piece of machinery, but also the manner in which he has been able to guide them through a difficult construction process. For Richter himself, the challenges of working on an isolated island, in sometimes trying conditions, have been great, but so too have the rewards. ‘Cape Wickham has been one of the hardest golf courses I’ve worked on,’ he says, ‘but it’s also the best, which makes it exciting.’

When green fee paying visitors arrive at Cape Wickham in 2015, evidence of Richter’s talent will be visible across the golf course. Most will inevitably focus on the spectacular holes and the spectacular stretches, such as 1-5, 9-12 and 14-18, but his greatest achievement might be the shaping of artificial areas to appear naturally occurring. One senses that he has enjoyed building the soft bumps and ridges on the ground as much as the wild and complicated green complexes by the ocean.

As modest and humble as they come, Lindsay Richter is rightly proud of his work on King Island and dreading of the day when he has to move from the sand and sea back to a residential project on a flat, clay-based landform. ‘I’m going to hate it’ he says. ‘Those courses are quicker to build, but these are much more fun. Plus they give you a great deal of satisfaction. No matter what I do from here, Cape Wickham is the course that I will look back on and say, ‘I did that’.’

Darius Oliver

Note: Darius Oliver is the author of Planet Golf, and a co-designer of the Cape Wickham golf course.

More News

Who Really Designed Cape Wickham Links?

AGD ranks Cape Wickham #1 in Australia & interviews Duncan Andrews to get full story on course design

Cape Wickham Links – The Inside Design Story

Co-designer Darius Oliver reveals the truth behind the design of Australia’s premier modern golf course

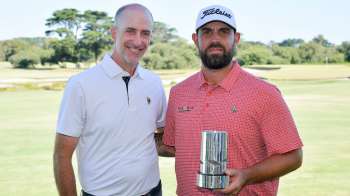

Ryan Peake pips David Micheluzzi in Sandbelt Invitational play-off

For the first time, extra holes were required to decide the Sandbelt Invitational winner at Royal Melbourne

Golf Membership in Australia grows for the fifth consecutive year

New report reveals golf continues to grow in Australia, with a record amount of adults (3.8 million) playing in 2023-24